Woodham's Railway Scrap Yard

The story of the legendary scrap yard of Woodham Brothers at Barry is a truly remarkable one. The man who fostered the legend, Dai Woodham, became a name familiar with steam enthusiasts and preservationists alike. Born in 1919 as David Lloyd Victor Woodham, Dai helped run the family's docks portering business. Barry had been developed as a major port for the export of coal due to the fact that Cardiff, the main port of export, could not cope with the vast quantities being shipped. Such was the success of Barry Docks that it still holds the record for the amount of coal exported in one year - 11 million tons in a single twelve month period.

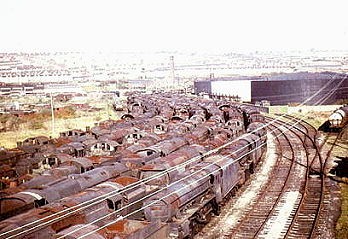

In the late 1930's, Woodham's interests turned to road transport and scrap, but it was not until 1957 that the company began dismantling railway wagons as a result of the 1955 Modernisation Plan which sought to reduce British Railways wagon fleet from 1¼ million to just 600,000 and to scrap 16,000 steam locomotives. The scrapping of that quantity of wagons by itself was set to transform the family business by providing a seemingly never-ending flow of material. The replacement of the 16,000 steam locomotives was a fundamental change of direction for British Railways and was going to take some time to implement. At first progress was limited to the replacement of those older steam designs employed on shunting and light branch duties as suitable diesel shunting locomotives and the first generation of diesel multiple units were already available for traffic, while a successful fleet of large main line engines still had to be designed and built. By 1958 a re-appraisal by the British Transport Commission resulted in the decision to accelerate the disposal of the steam fleet. This far-reaching decision soon led to large groups of condemned locomotives arriving at the major BR works for cutting-up and frequently the yards at the works could not cope with storage of such an enormous quantity of engines. Consequently, dumps of withdrawn locomotives began to appear in adjacent sidings or nearby closed branch lines. Within a very short time the rate of withdrawals was outstripping the capacity of the main works to dispose of them. So, it was decided to put out to tender the majority of locomotives to the private scrap yards in an attempt to clear the backlog at the works and its maiden customer became Woodham Brothers of Barry.

On the 25th of March 1959, the first batch of engines was despatched to Barry. Although the number of locomotives bought by Woodham's was comparatively small at this stage, the size of the deliveries increased and between November 1960 and April 1961 alone, 40 locomotives were acquired from Swindon. Most of these engines were scrapped soon after their arrival, but as the number of deliveries increased, additional storage was found at the low-level sidings adjacent to the oil terminal and also on sidings built on the site of the former West Pond.

During 1965, 65 locomotives arrived at the Barry

scrap yard, however, in the first six-month period 28 engines were dismantled but cutting virtually ceased from the autumn onwards

as the scrap men concentrated instead on breaking up yet more freight wagons and brake vans. Dai Woodham continued to purchase further

locomotives until the end of steam in 1968 with many of the later deliveries being of the BR Standard designs. Altogether from 1959

until 1968, 297 locomotives were bought by Woodhams, however by August 1968, 217 remained at the Barry scrap yard. It was at this time

that steam locomotive enthusiasts realised that they had to be content with the National Collection accompanied by a relatively small

number of privately-purchased locomotives such as 'Flying Scotsman', 'Clun Castle' and the Bluebell Railway fleet, but many classes had

already become extinct and the only other source of steam engines for the future was to be this new phenomenon at Barry. The railway

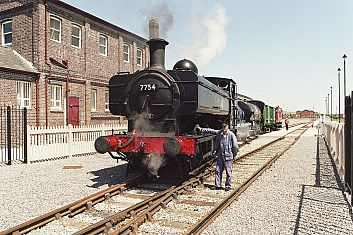

preservation boom began. In the mid-1970s the mass exodus began. Nobody at this stage thought that many of the Barry locomotives would be

saved and certainly not the 213 engines that were eventually moved to pastures new.

During 1965, 65 locomotives arrived at the Barry

scrap yard, however, in the first six-month period 28 engines were dismantled but cutting virtually ceased from the autumn onwards

as the scrap men concentrated instead on breaking up yet more freight wagons and brake vans. Dai Woodham continued to purchase further

locomotives until the end of steam in 1968 with many of the later deliveries being of the BR Standard designs. Altogether from 1959

until 1968, 297 locomotives were bought by Woodhams, however by August 1968, 217 remained at the Barry scrap yard. It was at this time

that steam locomotive enthusiasts realised that they had to be content with the National Collection accompanied by a relatively small

number of privately-purchased locomotives such as 'Flying Scotsman', 'Clun Castle' and the Bluebell Railway fleet, but many classes had

already become extinct and the only other source of steam engines for the future was to be this new phenomenon at Barry. The railway

preservation boom began. In the mid-1970s the mass exodus began. Nobody at this stage thought that many of the Barry locomotives would be

saved and certainly not the 213 engines that were eventually moved to pastures new.

The price of each locomotive was set at its equivalent scrap value. Woodhams kept a complete breakdown of the amount and different

types of metal that each locomotive contained. By applying the 'going rate' for steel or copper scrap to the known weights, a realistic

price was calculated. There were liabilities that affected both Woodhams and the buyers. One of the many contract conditions entered

into by the private scrapyards and BR was that locomotives sold for scrap could not be resold. This was primary to stop less scrupulous

dealers buying an engine at scrap value and then selling it on at a highly inflated price to a private railway or preservation society.

BR charged a levy - that had to be added to the purchase price - for complete locomotives sold by Woodhams, although this charge was

eventually abandoned. Another burden, this time paid by Dai, was the rental charge for the yard at Barry paid to Associated British Ports

for each locomotive, for each year. Although some locomotives were fully paid for but remained at the yard while preservationists worked

on the engines, it all had to come from Dai's own pocket. But one charge that would alter prices substantially was the introduction of

VAT in 1973.

As the 1970's progressed the number of rescue attempts became fewer and with the uncertainty of continued wagon supplies, the 100 or so locomotives in the yard that remained unpurchased looked to be in a vunerable position. By this time examples of all the classes that had survived in the yard were to be found elsewhere, but numerous people felt that not only would it be desirable to save as many of the locomotives that remained at Barry, but that they would also be needed on the existing and the proposed private lines around the country.

Following much correspondence in the railway press, a group of like-minded people met on the 10th of February 1979 to review the options available. The outcome was the formation of the 'Barry Steam Locomotive Action Group' with the simple objective of securing the future of as many of the locomotives at Barry scrapyard. Headed by Francis Blake, they began by increasing awareness of the locomotives and their types in the yard, to liase with prospective purchasers and with the scrapyard, and to put people in touch with one another, particularly those who wanted to contribute to - or purchase jointly - any of the remaining locomotives.